¿CUÁNTA ENERGÍA RENOVABLE NO CONVENCIONAL PUEDE INTEGRAR UN SISTEMA ELÉCTRICO?

- 26 de junio de 2019

[tp lang=»es» not_in=»en»]

Fuente: Energía Estratégica

Columna de Opinión Oscar Ferreño

Anteriormente mencionamos la necesidad de integrar energías renovables no convencionales (ERNC) en los sistemas eléctricos para disminuir las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero. También comentamos que las ERNC más importantes (la eólica y la solar) no son gestionables, y que se deben considerar como una demanda negativa y que la demanda neta resultante puede, en algunos momentos, ser más variable y menos predecible que la demanda total. Por lo anterior, decíamos que era necesario disponer de energías convencionales más flexibles hasta que las tecnologías de almacenamiento se volviesen más competitivas.

Ahora bien, ¿cuánta eólica o solar puede soportar un sistema eléctrico sin almacenamiento y sin presentar problemas de gestión? Una primera respuesta es que el sistema puede absorber tanta potencia de ERNC como cantidad tenga instalada de hidroeléctricas. Esta afirmación, que es más bien una llamada “regla de pulgar”, se basa en la flexibilidad de operación que presentan las hidroeléctricas, cuya rapidez para tomar o dejar carga unida a su capacidad de almacenar energía en sus embalses permite a estas copiar perfectamente las variaciones de la demanda neta. Se destaca que aún las centrales hidroeléctricas de pasada, es decir las que no tienen embalse, igualmente tienen capacidad de almacenamiento de al menos algunas horas.

Esto ubicaría a Argentina con una capacidad de admitir unos 15.000 MW de ERNC.

Esta “regla de pulgar”, si bien es efectiva en cuanto a la estabilidad del sistema eléctrico, no es tan cierta en cuanto a la cantidad económicamente óptima de ERNC. Es decir, se puede correr el riesgo de una sobreinversión en el parque de generación. Como las ERNC no son gestionables, un exceso de estas puede producir un derrame eólico o solar. Por ejemplo, si instalamos una potencia eólica equivalente a la potencia máxima demandada por el sistema es obvio que el viento pude hacer que se produzca la potencia máxima de la eólica en un momento que la demanda no sea la máxima, y entonces estaríamos ante un “derrame eólico”.

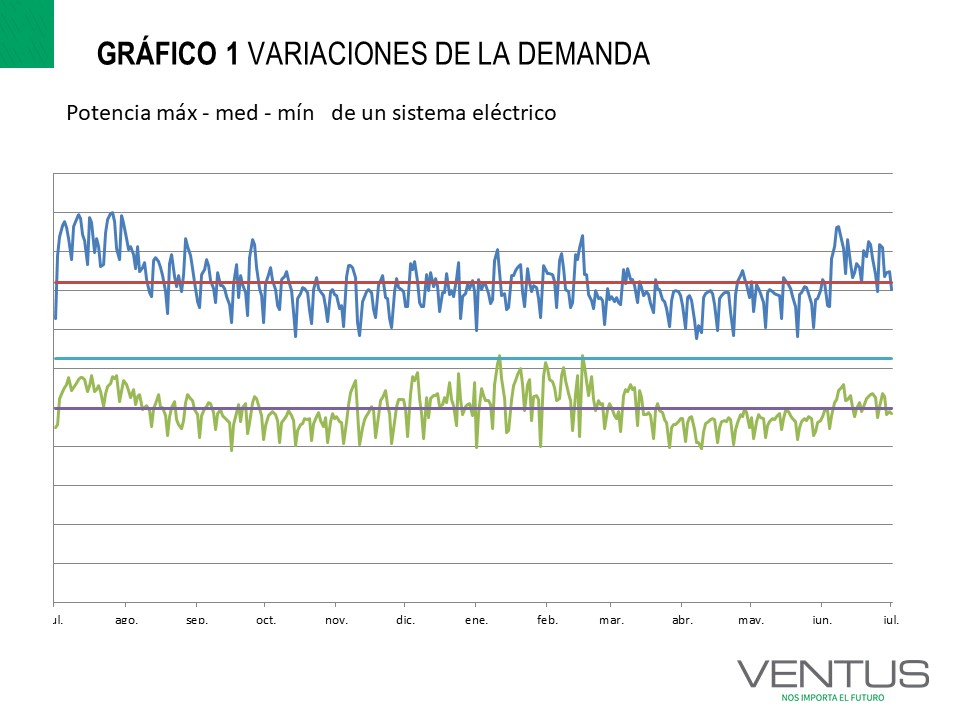

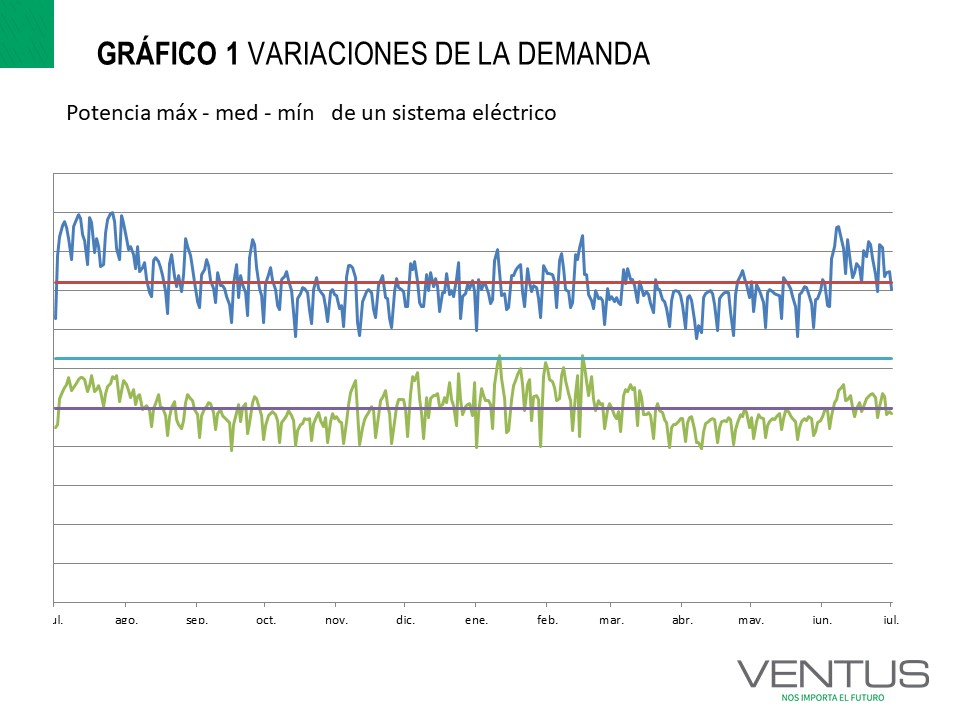

La demanda total es continua y variable, instante a instante, presentando un máximo y mínimo diario. Estos, a su vez, presentan máximos y mínimos semanales, mensuales y anuales. La energía media anual vendría representada por una potencia media equivalente más o menos al promedio entre el máximo y mínimo anual (Gráfico 1).

Si la potencia instalada de ERNC es cercana a esa potencia media anual entonces el derrame de ERNC seria mínimo o prácticamente nulo.

Los alrededor de 100.000 GWh anuales de Argentina representan una potencia media de algo más de 11.000 MW.

¿Y cuánto representaría esa energía proveniente de ERNC?

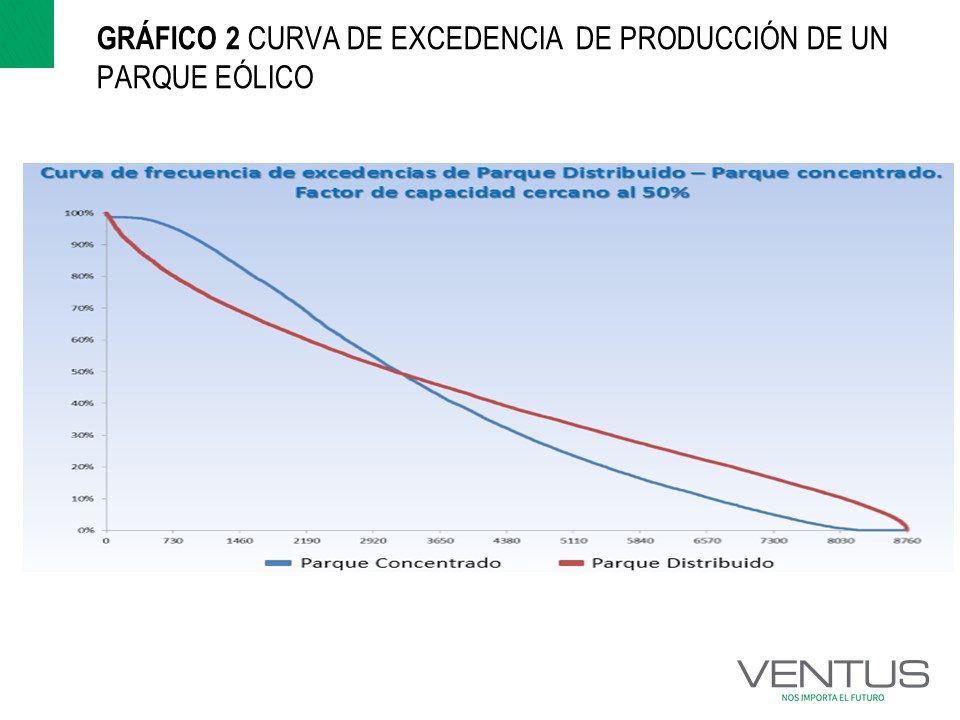

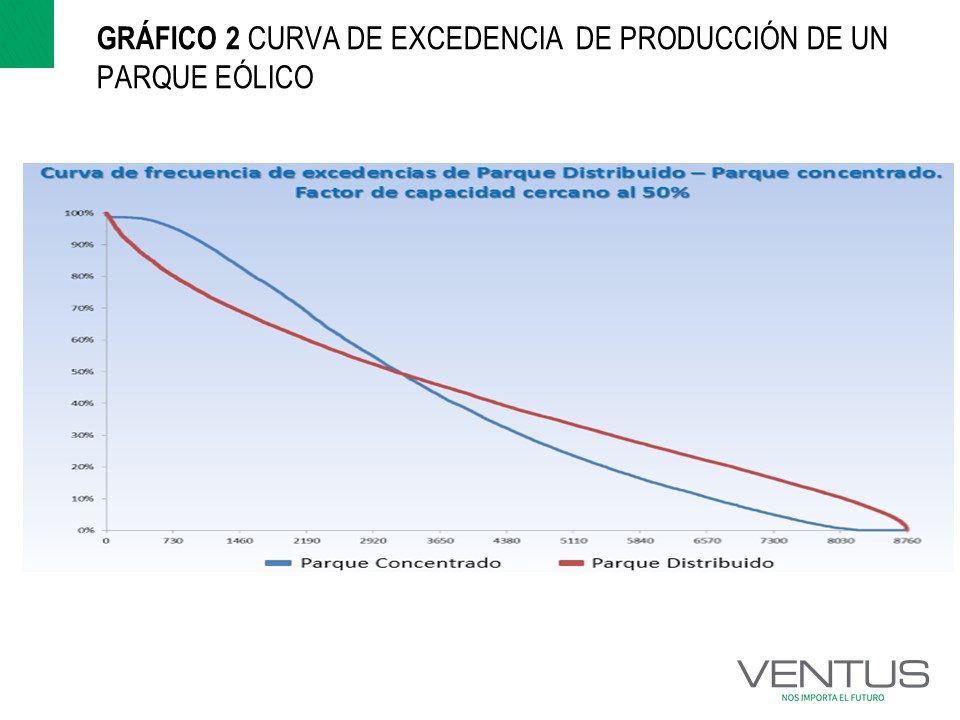

Si se trata de energía eólica que esté distribuida en una región, y hacemos una gráfica de probabilidad de excedencia colocando al principio las potencias más altas, vemos que tenemos un comportamiento en forma triangular. Es decir, pocos eventos con los parques produciendo a plena potencia, pocos eventos con potencia nula y el resto alineados, la energía de estos parques sería el área bajo la curva. Si se trata de parques eólicos en Argentina estaríamos en un factor de capacidad teórico de 50% (Gráfico 2)

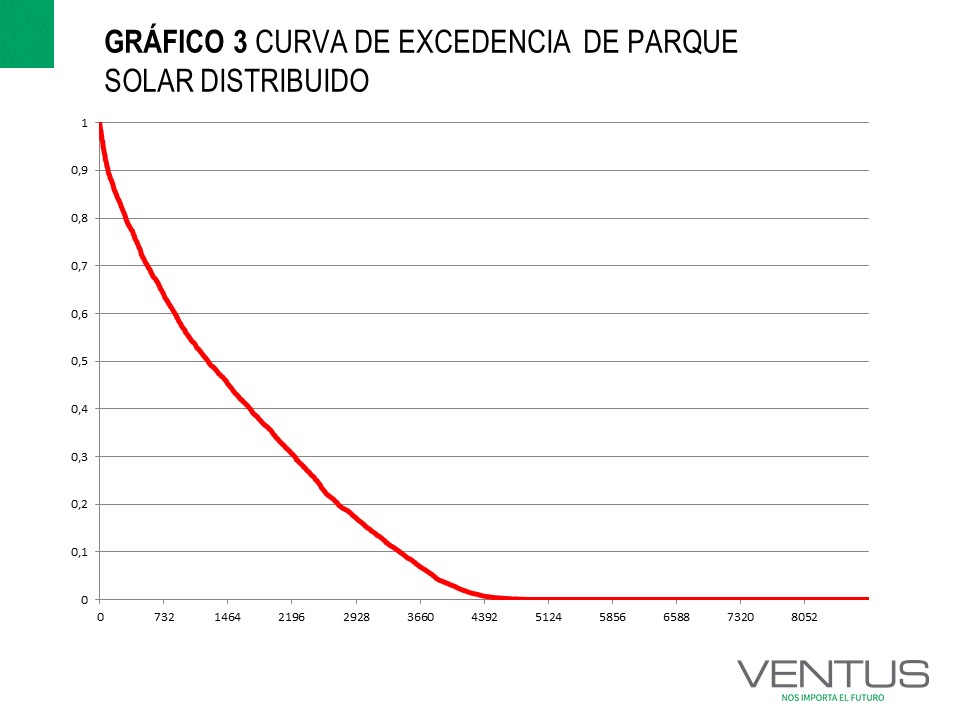

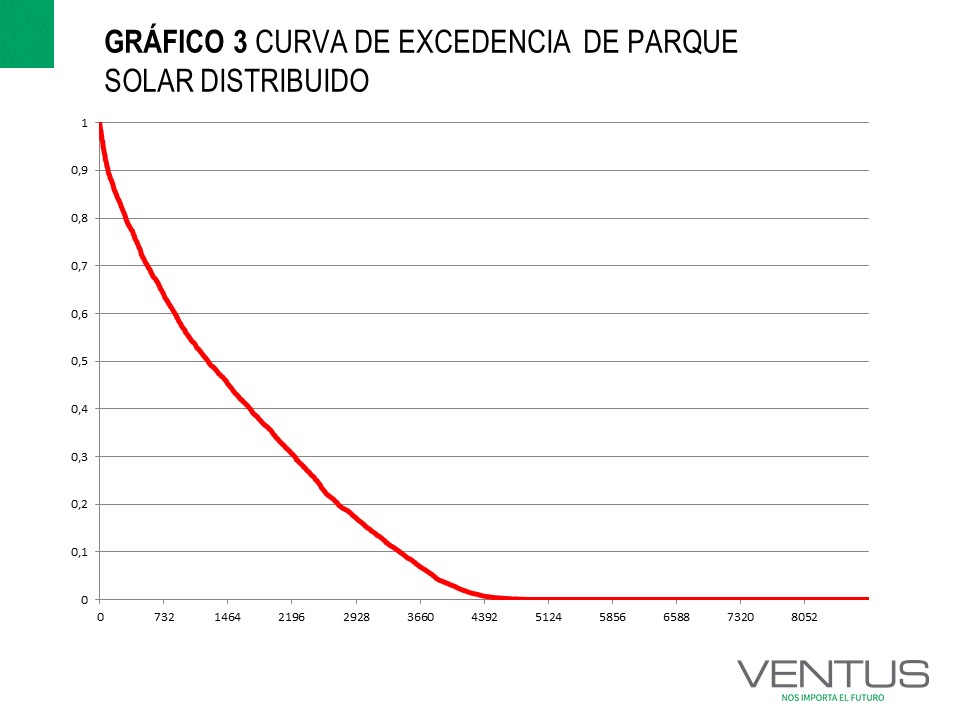

Si se trata de parques solares, obviamente la mitad de estos eventos serían en horas nocturnas y no produciría energía. En este caso, el factor de capacidad teórico sería de un 25% (Gráfico 3).

If it is a combination of solar and wind farms (say 40/60), the capacity factor would be 40%.

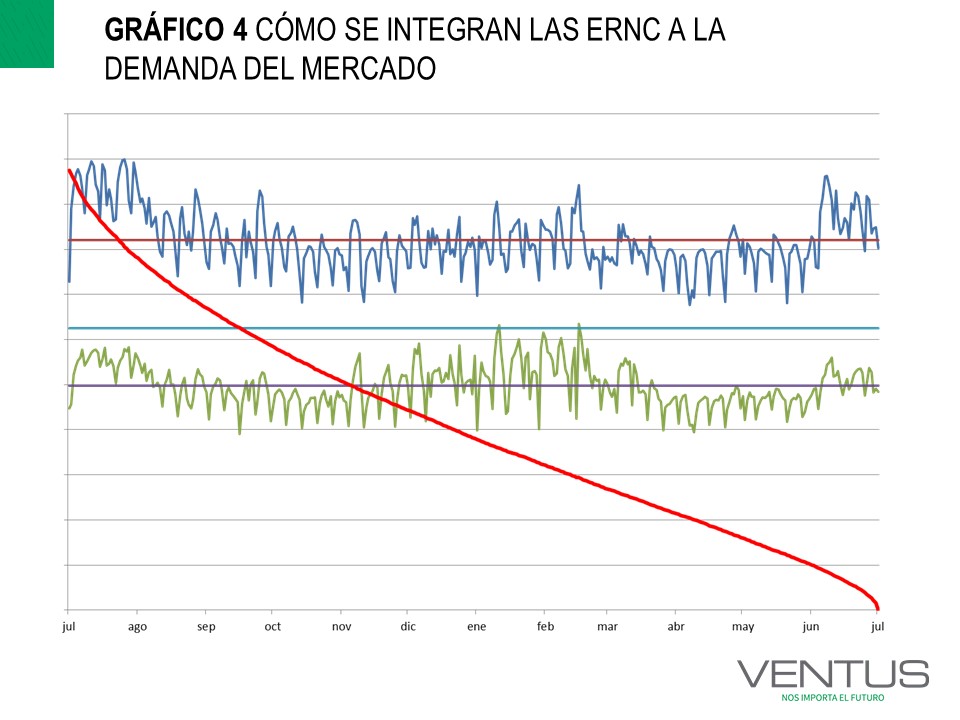

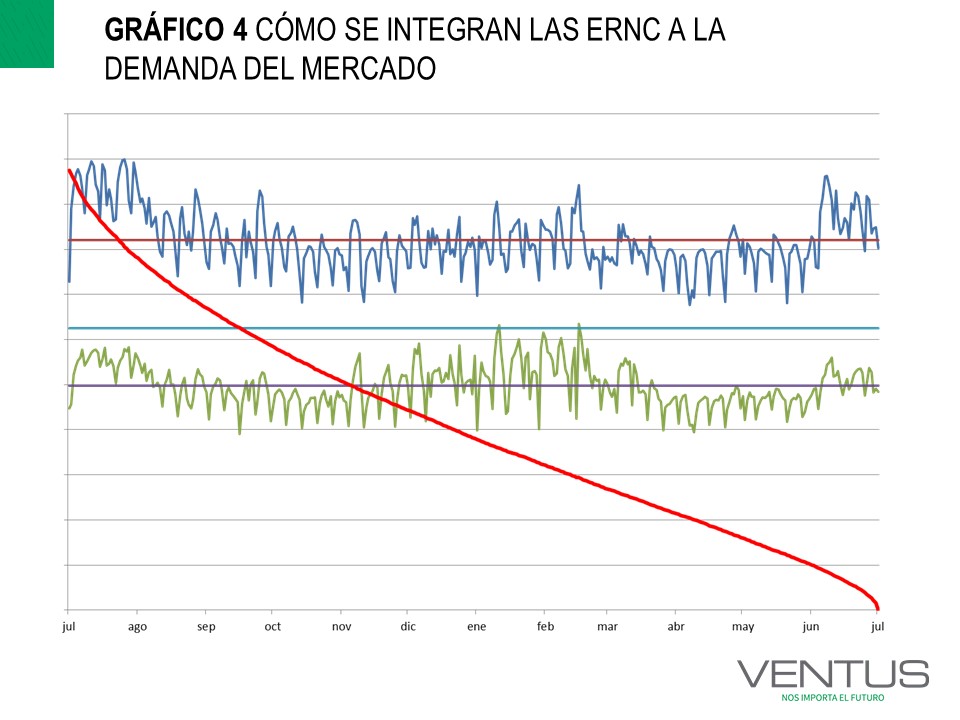

Therefore, if we install a quantity of NCRE equivalent to the average demand power, we can, without producing unmanageable NCRE spills, cover 40% of the demand (Graph 4).

En resumen, parecería que en las condiciones actuales Argentina podría instalar entre 10.000 y 11.000 MW de ERNC sin mayores problemas de gestión. Estas ERNC cubrirían un 40 % de la demanda y, junto con las grandes hidroeléctricas, se podría cubrir hasta el 80 % de la demanda con energía renovables.

Mejoras en la infraestructura de transmisión y la progresiva instalación de capacidad de almacenamiento en el sistema (ya sea centrales hidroeléctricas reversibles o baterías estacionarias) permitirán seguir cubriendo el crecimiento de la demanda con más instalación de ERNC y mejorar aún más los porcentajes de participación de estas tecnologías.

[/tp]

[tp lang=»en» not_in=»es»]

Source: Energía Estratégica

Opinion Column

Previously, we mentioned the need to integrate non-conventional renewable energies (NCRE) in the electric system to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We also commented that the most important NCRE (wind and solar) are not manageable, and that they should be considered as a negative demand and that the resulting net demand may, at some moments, be more variable and less predictable than the total demand. Therefore, we said that it was necessary to have more flexible conventional energies until the storage technologies became more competitive.

Now, how much wind or solar energy can support an electrical system without storage and without presenting management problems? A first answer is that the system can absorb as much NCRE power as the amount of hydroelectric plants installed. This statement, which is the so-called «thumb rule», is based on the flexibility of operation presented by hydroelectric plants, whose rapidity to take or leave load together with their capacity to store energy in their reservoirs allows them to copy perfectly the variations in the net demand. It is pointed out that even run-of-the-river hydroelectric power plants, also have a storage capacity of at least a few hours.

This would place Argentina with a capacity to admit more than 15,000 MW of NCRE.

This «thumb rule», while effective in terms of the stability of the electrical system, is not so convenient in terms of the economically optimal amount of NCRE. An excess of these can produce a wind or solar spill. For example, if we install a wind power equivalent to the maximum power demanded by the system, it is obvious that the wind could produce the maximum power at a time when the demand is not the maximum, and then we would be facing a «wind spill».

The total demand is continuous and variable, instant to instant, presenting a maximum and minimum daily. These, present maximums and minimums weekly, monthly and annualy. The average annual energy would be represented by an average power equivalent more or less the average between the annual maximum and minimum (Figure 1).

If the installed capacity of NCRE is close to that annual average power, then the ERNC spill would be minimal or practically nul.

The annual 100,000 GWh of Argentina represents an average power of over 11,000 MW.

How much would that energy represent from NCRE?

If it is wind energy that is distributed in a region, and we make a probability of exceedance graph by placing the highest power at the beginning, we see that it behaves in triangular form. That is, few events with the parks producing at full power, few events with zero power and the rest aligned, the energy of these parks would be the area under the curve. If it is about wind farms in Argentina we would be at a theoretical capacity factor of 50% (Graph 2)

If it is solar farms, obviously half of these events would be at night and would not produce energy. In this case, the theoretical capacity factor would be 25% (Graph 3).

If it is a combination of solar and wind farms (say 40/60), the capacity factor would be 40%.

Therefore, if we install a quantity of NCRE equivalent to the average demand power, we can, without producing unmanageable NCRE spills, cover 40% of the demand (Graph 4).

It would seem that under current conditions Argentina could install between 10,000 and 11,000 MW of NCRE without major management problems. These NCREs would cover 40% of the demand and, together with the large hydroelectric plants, up to 80% of the demand could be covered with renewable energy.

Improvements in the transmission infrastructure and the progressive installation of storage capacity in the system (either reversible hydroelectric plants or stationary batteries) will allow us to continue covering the growth of demand with more installation of NCRE and improve the participation percentages of these technologies.

[/tp]